Jamie Ryan Pillette5

1Troubles de la communication, Université de Louisiane, Lafayette, États-Unis.

2Ophtalmologie et sciences visuelles, Programme d’études supérieures en médecine expérimentale, Université de la Colombie-Britannique, Vancouver, Canada.

3Groupe de recherche sur la dynamique neuronale, Vancouver, Canada.

4Kenya Catholic Doctors Association, Nairobi, Kenya.

5Université de Louisiane, Lafayette, États-Unis.

DOI: 10.4236/oalib.1103937PDFHTML XML 8 156 Téléchargements 78 119 Vues Citations

En 1993, l’OMS a annoncé un « vaccin contraception » pour la « planification familiale ». Des recherches publiées montrent qu’en 1976, des chercheurs de l’OMS avaient conjugué l’ande tétanos (TT) avec la gonadotrophine chorionique humaine (hCG) produisant un vaccin « contraception ». La conjugaison de la TT avec l’hCG provoque l’attaque des hormones de grossesse par le système immunitaire. Les résultats attendus sont des avortements chez les femmes déjà enceintes et/ou l’infertilité chez les receveurs non encore imprégnés. Les inoculations répétées prolongent l’infertilité. Actuellement, les chercheurs de l’OMS travaillent sur des vaccins anti-fertilité plus puissants utilisant de l’ADN recombinant. Les publications de l’OMS montrent un objectifà long risquede réduire la croissance démographique dans les « pays moins développés » instables. En novembre 1993, des publications catholiques ont paru disant qu’un vaccin abortif était utilisé comme prophylactique contre le tétanos. En novembre 2014, l’Église catholique a affirmé qu’un tel programme était en cours au Kenya. Trois laboratoires de biochimie indépendants accrédités à Nairobi ont testé des échantillons de flacons du vaccin antitétanique de l’OMS utilisé en mars 2014 et ont trouvé de l’hCG là où aucun ne devrait être présent. En octobre 2014, 6 flacons supplémentaires ont été obtenus par des médecins catholiques et testés dans 6 laboratoires accrédités. Encore une fois, l’hCG a été trouvée dans la moitié des échantillons. Par la suite, le laboratoire AgriQ Quest de Nairobi, dans deux séries d’analyses, a de nouveau trouvé de l’hCG dans les mêmes flacons de vaccin qui ont été testés positifs plus tôt, mais n’a trouvé aucune hCG dans 52 échantillons présumés par l’OMS être des flacons du vaccin utilisé dans la campagne Kenya 40 avec les mêmes numéros de lot d’identification que les flacons qui ont été testés positifs pour l’hCG. Étant donné que l’hCG a été trouvée dans au moins la moitié des échantillons de vaccins de l’OMS connus par les médecins impliqués dans l’administration des vaccins pour avoir été utilisés au Kenya, notre opinion est que la campagne « anti-tétanos » du Kenya a été raisonnablement remise en question par l’Association des médecins catholiques du Kenya en tant que façade pour la réduction de la croissance démographique.

Mots-clés

Mesures anti-fertilité, Gonadotrophine chorionique bêta-humaine, Vaccin contraceptif, Programmes de contrôle de la population

Partager et citer :Oller, J. , Shaw, C. , Tomljenovic, L. , Karanja, S. , Ngare, W. , Clement, F. et Pillette, J. (2017) HCG Found in WHO Tetanus Vaccine in Kenya Raises Concern in the Developing World. Open Access Library Journal, 4, 1-32. doi: 10.4236/oalib.1103937.

Le 6 novembre 2014, la Conférence des évêques catholiques du Kenya (KCCB) qui préside la Commission catholique de la santé du Kenya (créée en 1957 [1] ) a publié un communiqué de presse alléguant que l’Organisation mondiale de la santé (OMS) utilisait secrètement un vaccin « contraceptif » dans sa campagne de vaccination antitétanique au Kenya 2013-2015 [2]. Quelques jours plus tard, un article du Washington Post a suivi avec des allégations similaires citant l’Association des médecins catholiques du Kenya (KCDA) [3]. De telles affirmations provenant de sources au sein de l’Église catholique ont motivé cette étude de cas de la campagne « anti-tétanos » de l’OMS au Kenya ainsi qu’un examen de la recherche de l’OMS pour développer des vaccins anti-fertilité1. De nombreux articles publiés, que nous avons trouvés dans les bases de données Web of Science et PubMed, documentent la recherche expérimentale de l’OMS avec divers conjugués vaccinaux anti-fertilité [4] – [24] depuis les années 1970. L’objectif publié des chercheurs de l’OMS effectuant les expériences était de concevoir un ou plusieurs vaccins « contraceptifs » qui peuvent, avec une fiabilité connue, produire et maintenir l’infertilité indéfiniment.

En arrière-plan, en tant que sous-unité des Nations Unies, l’OMS a également poursuivi l’objectif mondial de réduire la croissance démographique mondiale principalement par le biais de la « planification familiale » et de la contraception [25]. Dans cet article, nous nous concentrons principalement sur un seul des vaccins contraceptifs de l’OMS [10] [16] [26] et plus particulièrement sur les spéculations sur le fait qu’il ait été déployé ou non par l’OMS dans les cinq administrations de vaccin contre le tétanos dans le cadre de la campagne 2013-2015 au Kenya. Nous examinons ici les recherches pertinentes et les meilleures données de laboratoire dont nous disposons afin de faire notre meilleure supposition, l’opinion éclairée dans laquelle les auteurs sont d’accord, concernant ce que l’OMS a pu réellement faire dans la campagne de vaccination récemment achevée au Kenya. Reconnaissant dès le départ que notre enquête implique des inférences à partir de données incomplètes et partielles, nous sommes d’avis que toutes les parties impliquées dans le travail de « planification familiale » de l’OMS doivent être pleinement informées.

Parce que, comme nous le rapporterons ici, certains des échantillons du vaccin contre le « tétanos » utilisé par l’OMS au Kenya testé par le KCCB/KCDA contenaient une composante « contrôle des naissances » de l’OMS, des questions éthiques et morales doivent être soulevées [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] . Le premier d’entre eux est la mise en garde « ne pas nuire » [32] . Si, comme le soupçonnaient les médecins catholiques [33] [34], les futures mères étaient induites en erreur en acceptant un vaccin antifertilité dans l’espoir de protéger leurs futurs enfants du tétanos néonatal, la « mise en garde contre le fait de ne pas nuire » a été violée. En recevant jusqu’à cinq injections d’antifertilité, toute future mère serait presque certainement privée des enfants mêmes qu’elle essayait de protéger du tétanos néonatal. Si les soupçons étaient valables, il y aurait également violation éthique de l’obligation de la part de l’OMS d’obtenir le « consentement éclairé » de ces filles et femmes kenyanes [35] [36] [37] [38] . Si le patient est conscient et compétent, les risques connus sont universellement censés être divulgués [37]. Le principe sous-jacent en cause se résume en fin de compte à la « règle d’or » de traiter les autres comme nous voudrions nous-mêmes être traités [39] [40] . Les adolescentes et les femmes matures ont-elles le droit de savoir si elles sont sur le point de recevoir un vaccin anti-fertilité? Ou, alternativement, l’OMS a-t-elle la prérogative d’administrer un tel vaccin comme prophylactique contre le tétanos sans divulguer son aspect anti-fertilité?2

Le type de vaccin antitétanos « contraceptif » que le KCCB et le KCDA soupçonnaient l’OMS d’utiliser au Kenya implique la liaison de la partie bêta de l’hormone hCG avec l’agent actif dans les vaccins contre le tétanos qui est l’anone tétanos (TT). En fait, les chercheurs biomédicaux de l’OMS travaillent à la conception d’un tel vaccin « anti-fertilité » pour le « contrôle des naissances » au moins depuis 1972. Des recherches publiées en 1976 ont confirmé que les receveurs d’un vaccin contenant du βhCG chimiquement conjugué avec du TT développent des anticorps non seulement contre le TT, mais aussi contre le βhCG. Le résultat, rapporté pour la première fois par des chercheurs de l’OMS lors d’une réunion de l’Académie nationale des sciences des États-Unis [5], est un vaccin « contraceptif » qui diminue le βhCG essentiel à une grossesse réussie et provoque au moins une « infertilité » temporaire. Des recherches ultérieures ont montré que des doses répétées peuvent prolonger l’infertilité indéfiniment [6] [8] [10] [11] [13] [14] [23] [24] [26] [50] . Dans les essais cliniques rapportés [10] [13] [14] , les chercheurs ont systématiquement évité d’administrer un vaccin « anti-fertilité » à une femme enceinte sur la théorie selon laquelle il provoquerait un avortement comme il le fait dans les modèles animaux expérimentaux [26] .

L’hormone hCG entière se compose de deux sous-unités liées appelées α (alpha-hCG) et β (bêta-hCG). Il est produit en quantités croissantes [51] [52] [53] , si tout va bien, par l’œuf fécondé qui se divise rapidement. La présence de βhCG permet le maintien du corps jaune en veillant à ce qu’il continue à produire suffisamment de progestérone nécessaire à l’implantation et à l’entretien, en particulier tout au long du premier trimestre. Une implantation réussie au jour 4 – 7 après la fécondation nécessite des quantités et un moment assez précis de la production de progestérone [5] [10] [11] [13] [16] [22] qui dépend à son tour d’une quantité suffisante de βhCG.

Étant donné que des quantités croissantes de βhCG sont essentielles à la « diaphonie » nécessaire pour maintenir la grossesse précoce, un vaccin contenant un conjugué TT / βhCG peut non seulement empêcher l’implantation d’un ovule fécondé, mais si un embryon est déjà implanté, un tel vaccin peut causer sa mort. Le résultat de toute perte de grossesse inexpliquée (non diagnostiquée) est communément appelé avortement « spontané » [54] . Cependant, si la perte était causée par un vaccin « contraceptif », représenté, comme le soupçonnaient les médecins catholiques au Kenya, uniquement comme un « prophylactique du tétanos », la mort du bébé serait due à la promesse trompeuse d’une naissance vivante sans tétanos. Par conséquent, si les soupçons de la KCCB et de la KCDA étaient valables, de nombreuses futures mères kenyanes sans méfiance, encouragées par l’OMS à assurer un avenir meilleur à un ou plusieurs de leurs propres enfants encore à naître, étaient en fait trompées pour soumettre leur corps à une ou plusieurs injections qui empêcheraient leurs propres bébés à naître.

Over the decades since the prototype of the WHO anti-βhCG vaccine was first tested in 1974 [5] , the volume of published research on anti-fertility vaccines has greatly increased. Although WHO researchers claim their TT/βhCG birth-con- trol vaccine is reversible [11] [55] , their on-going research aims to produce a recombinant gene using DNA of either E. Coli [21] or vaccinia virus [9] . Given the power of recombinant DNA to reproduce, long-lasting or even permanent sterility in vaccinated recipients is theoretically attainable.

2. Methodologies and Materials

Following the news reports in 2014 from the KCCB and KCDA claiming that the WHO vaccination campaign advertised to “eliminate maternal and neonatal tetanus” [56] [57] [58] [59] [60] was suspected of vectoring a birth-control product into women of child-bearing age [3] [31] [45] , some of us3 began searching the Web of Science for published research concerning “anti-fertility vaccine”, “birth-control vaccine”, and for “tetanus toxoid AND human chorionic gonadotropin” (sometimes following up titles in the PubMed database). Our question, was whether the WHO was engaged in developing a birth-control vaccine linking TT to βhCG [5] [61] ? What was the research basis, if any, for the KCDA suspicions that the WHO might be using an anti-fertility vaccine in Kenya?

We found a plethora of studies beginning with the linking of TT to βhCG by WHO researchers in the 1970s. We also found policy statements by the WHO and its collaborators stating the geo-political and economic goal of population growth reduction in unstable “less developed countries” (including Kenya), known to be rich in costly mineral resources needed by the developed nations. These initial findings gave credence to the suspicion that the WHO may have disguised a clinical trial of their “birth-control vaccine” in Kenya as an effort to “eliminate maternal and neonatal tetanus” there.

Given the published research confirming the history of the WHO “birth- control” vaccine, the American and Canadian co-authors decided to contact Dr. Wahome Ngare who had been quoted in some of the published reports about the WHO campaign in Kenya. He put the rest of us in touch with Dr. Stephen Karanja, another of the physicians required by the Kenya Ministry of Health to participate in the WHO vaccination campaign. They agreed to join us as co-authors and to provide access to the data from laboratory tests of the vaccine being used in the Kenya campaign. Together with the KCDA they have assured us of the integrity of the chain of custody of the particular samples (carefully apportioned “aliquots”) of WHO vaccine that they were personally involved in collecting, apportioning, and distributing to accredited Nairobi laboratories. In this report, we merely summarize the results of the laboratory tests now in the public domain. We also provide access to all three of the reports presented to the WHO and Ministry of Health in Kenya by the KCCB of the results obtained from the several laboratories [62] [63] [64] . While none of us can verify the chain of custody of the tested aliquots handled by the various laboratories and their employees, however, we hold the opinion based on data in hand, that at least half of the vaccine samples actually obtained from vials being used in the March and October rounds in 2014 tested positive for βhCG.

With all the foregoing in mind, we pursued a five-fold approach in our investigative research. In the following bolded list, we summarize each of our five methodologies with bolded titles corresponding to the five distinct segments by the same titles presented respectively in the Results section that immediately follows the list:

1) Documenting the history and goals of the WHO. Various geo-political and economic reports, and policy statements from the WHO, the United Nations, and affiliated governmental agencies (in particular the U. S. Agency for International Development) set a high premium on contraception for “family planning” in certain “less developed” regions of the world.

2) Examining the published scientific research. News reports from the Catholic Church about the WHO vaccination campaign going on in Kenya spurred us to seek out the published research in professional journals. Was it true that the WHO had been engineering vaccines linking TT with βhCG? This methodology led us to a trail of published research beginning around 1972 growing into many publications cited thousands of times showing that the WHO has been pursuing contraceptive vaccine research as claimed by the KCDA.

3) Tracking the reported events in Kenya. Our third methodology was a form of investigative journalism. Materials consisted of the news reports coming from Kenya set in chronological order with information from the two preceding methodologies on the theory that concordance between such different streams of information is unlikely to occur by chance.

4) Comparing vaccination schedules for tetanus and anti-fertility. Our fourth method involved a “thought experiment” applying the simplest type of mathematical probative tests for a variety of Euclidean congruence [65] . The KCDA claimed that the WHO dosage schedule of five shots administered in six month increments was inconsistent with published tetanus vaccination schedules. So, our simple probative test was to compare the published vaccination schedules for TT, t, with the published schedules for TT/βhCG, β. Calling the schedule used in Kenya, k, and taking “=” to mean congruent, if t ≠ β, but β = k, and k ≠ t, it follows that k is a dosage schedule appropriate to TT/βhCG, the WHO antifertility vaccine. The simple test of congruence of dosage schedules is not conclusive proof by itself, but it is consistent with the opinion of the authors that the WHO followed a dosage schedule appropriate for TT/βhCG in Kenya but inappropriate for TT vaccine.

5) Analyses en laboratoire des vaccins de l’OMS. Avec l’aide de la KCDA, nous avons analysé les rapports réels des tests de laboratoire des flacons du vaccin kényan obtenus par la KCDA, comme l’ont garanti Ngare et Karanja, pendant la campagne de vaccination proprement dite. Ces résultats de laboratoire ont été systématiquement comparés à des analyses d’échantillons fournis ultérieurement par des responsables de l’OMS provenant prétendument de fournitures maintenues à Nairobi. Deux sources ont été testées : a) des flacons du vaccin obtenus par le KCDA parmi ceux administrés par l’OMS en mars et octobre 2014, et b) 52 flacons supplémentaires remis par l’OMS à partir des fournitures à Nairobi au « Comité mixte d’experts ». Parmi les échantillons que les co-auteurs Karanja et Ngare étaient personnellement responsables de manipuler, plus de la moitié se sont avérés contenir du βhCG par plusieurs laboratoires et dans de multiples tests distincts. Le KCDA a également donné accès aux rapports du domaine public et aux données techniques publiées pour une plus grande accessibilité ici pour la première fois dans un forum académique professionnel. Sur les 52 échantillons fournis par l’OMS au « Comité mixte », aucun ne contenait de βhCG, et parmi ceux-ci, 40 flacons livrés après un délai de 58 jours (du 11 novembre 2014 au 9 janvier 2015) par l’OMS, contenant prétendument le vaccin TT du Kenya, ont été testés négatifs pour le βhCG, mais avaient exactement les mêmes étiquettes de désignation que les 3 flacons obtenus par le KCDA lors des vaccinations ayant eu lieu en octobre 2014 qui ont testé positif pour le βhCG. Les divergences nécessitent des explications et sont traitées dans la section Discussion qui suit la section Résultats.

Dans cette section, nous discutons des résultats de chacune des méthodologies énumérées en les prenant dans l’ordre présenté dans la section précédente.

1) Documenter l’histoire et les objectifs de l’OMS

Nous avons trouvé des documents reliant des décennies de travail de l’Agence américaine pour le développement international (USAID) et des Nations Unies, l’organisation mère de l’OMS, faisant de la réduction de la croissance démographique mondiale, en particulier dans des régions comme le Kenya, un objectif central. L’OMS a été créée en 1945 et a immédiatement adopté l’idée que la « planification familiale », alias contrôle de la population, plus tard appelée « planning familial » [66], était une nécessité pour la « santé mondiale ». L’idée que la « réduction de la fertilité » était essentielle remonte à la première clinique de contrôle des naissances de Margaret Sanger aux États-Unis qui a été créée en 1916 [67] et a été poursuivie jusqu’à l’époque actuelle de la rédaction [68].

Parallèlement au lancement par l’OMS de recherches pour développer des vaccins anti-fertilité [5], sous la direction de Henry Kissinger, un rapport classifié était en cours d’élaboration sur la base d’études sur la croissance démographique antérieures de plusieurs décennies. Le rapport Kissinger [69], également connu sous le nom de US National Security Study Memorandum 200 [70] , expliquait les raisons géopolitiques et économiques de réduire la croissance démographique, en particulier dans les « pays moins développés » (PMA), à près de zéro. Ce rapport est devenu la politique officielle des États-Unis sous le président Gerald Ford en 1975 et traitait explicitement de « programmes de planification familiale efficaces » dans le but de « réduire la fertilité » afin de protéger les intérêts des pays industrialisés, en particulier des États-Unis, dans les ressources minérales importées (voir p. 50 dans [69] [70]). Bien que l’ensemble du plan ait d’abord été caché au public, il a été déclassifié par étapes entre 1980 et 1989. Entre-temps, alors que ce document était sur le point de devenir une « politique » officielle, le programme de recherche de l’OMS développant des vaccins « contraceptifs » a été lancé vers 1972 et présenté publiquement en 1976 [5], un an seulement après l’adoption du rapport Kissinger comme politique officielle.

La « politique » officielle appelait à « des efforts beaucoup plus importants pour contrôler la fécondité » (p.19dans [ 69 ] [70] ) dans le monde entier, mais surtout dans les « pays moins développés » (pp. 18-20 dans [69] [70] ). Le rapport Kissinger citait des documents sur « la croissance démographique et l’avenir américain » ainsi que sur « la population, les ressources et l’environnement » et ciblait spécifiquement les PDJ pour le « contrôle de la fertilité ». Certaines cibles des PMA justifiaient leurs réserves connues d’aluminium, de cuivre, de fer, de plomb, de nickel, d’étain, d’uranium, de zinc, de chrome, de vanadium, de magnésium, de phosphore, de potassium, de cobalt, de manganèse, de molybdène, de tungstène, de titane, de soufre, d’azote, de pétrole et de gaz naturel (voir p. 42 in [69] [70] ). Le lien entre les ressources minérales et le contrôle de la population (« planification familiale ») était dû au fait que les pays industrialisés devaient déjà importer des quantités importantes des minéraux nommés à un coût considérable et que le rapport Kissinger prévoyait que ces coûts augmenteraient certainement en raison de l’instabilité dans les PMA précipités par la croissance démographique (p. 41 dans [69] [70] ).

Le rapport Kissinger a également blâmé la croissance démographique pour la pollution bien avant le numéro de 2009 du Bulletin de l’OMS, où Bryant et al. [61] prédisaient une « augmentation significative des émissions de gaz à effet de serre » (p. 852). Cette publication de l’OMS a estimé une augmentation de la population mondiale d’environ 6,8 milliards de personnes en 2009 à 9,2 milliards d’ici 2050. Prolongeant cet argument de l’OMS, Bill Gates a exprimé en 2010 l’espoir que les vaccins ainsi que la « planification familiale » pourraient amener la croissance démographique à un proche de zéro [71]. Alors que Bryant et al. ont décrit les mesures anti-fertilité comme des « services de planification familiale volontaires », ils ont reconnu que ces « services » de l’OMS avaient été signalés comme trompant les personnes « servies » (pp. 852-853, 855) avec « des procédures de stérilisation appliquées sans le plein consentement du patient » [nos italiques] (p. 852). De même, une étude de 1992 intitulée Fertility Regulating Vaccines publiée par le Programme de formation à la recherche sur la reproduction humaine de l’ONU et de l’OMS a fait état de « cas d’abus dans les programmes de planification familiale » datant des années 1970, notamment :

incitations [nos italiques]∙∙∙ [Telles que] les femmes stérilisées à leur insu∙∙∙ étant inscrites à des essais de contraceptifs oraux ou d’injectables sans∙∙∙ consentement∙∙∙ [et] ne pas [être] informées des effets secondaires possibles de∙∙∙ le dispositif intra-utérin (DIU). (p. 13 à [72] )

Les auteurs de ce rapport de l’OMS ont déclaré que des expressions telles que « planification familiale » et « planification familiale » étaient plus acceptables pour le public. Ils ont choisi de ne pas mentionner les « mesures anti-fertilité pour le contrôle de la population ». Ils n’ont pas non plus pensé qu’il était sage de parler de « développement économique » (p. 13) dans les PNT riches en minéraux, ou de l’aide que les pays industrialisés pourraient apporter pour mettre ces ressources minérales sur le marché. S’exprimant au nom de l’OMS, Bryant et al. ont écrit « il est peut-être plus propice à une approche fondée sur les droits de mettre en œuvre des programmes de planification familiale [nos italiques] en réponse aux besoins de bien-être des personnes et des communautés plutôt qu’en réponse à la préoccupation internationale concernant la surpopulation mondiale » (p. 853 dans [61] ). Le message public de l’OMS devait porter sur la « santé » et la « planification familiale ». Cependant, le message d’espoir incluait parfois une référence aux vaccins « contraceptifs ». Par exemple, le 22 janvier 2010, il a été officiellement annoncé que la Fondation Bill et Melinda Gates avait engagé 10 milliards de dollars pour aider à atteindre les objectifs de réduction de la population de l’OMS, en partie grâce à de « nouveaux vaccins » [73] [74].

About a month later, Bill Gates suggested in his “Innovating to Zero” TED talk in Long Beach, California on February 20, 2010 that reducing world population growth could be done in part with “new vaccines” [71] . At 4 minutes and 29 seconds into the talk he says:

The world today has 6.8 billion people. That’s headed up to about 9 billion [here he is almost quoting Bryant et al.]. Now, if we do a really great job on new vaccines [our italics], health care, reproductive health services, we could lower that by, perhaps, 10 or 15 percent∙∙∙ [71]

Given the published intentions of the WHO and its collaborators concerning population growth reduction, we focus attention next on the published scientific literature from the Web of Science and PubMed about the WHO anti-fertility vaccine research programs.

2) Examining the published scientific research

A search on the Web of Science (and PubMed) for “tetanus toxoid AND beta hCG” led to publications by WHO researchers spearheaded by G. P. Talwar [4] – [24] . After his first report appeared in 1976 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [5] , the number of citations of the stream of publications emanating from that WHO research program would begin to grow exponentially. By August 5, 2016, the Web of Science database already pointed to 150 research publications citing the 1976 report while subsequent papers have now been cited many thousands of times. Figure 1 shows citations through 2015 of just one of the follow up papers by Talwar et al., this one from 1994 titled, “A vaccine that prevents pregnancy in women” [13] . It also appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and by January 9, 2016, according to the Web of Science, had already been cited 2538 times.

We focus attention next on findings from a forensic journalism methodology laying out the chronology connecting the WHO anti-fertility research agenda to the 2013-2015 vaccination campaign in Kenya.

3) Tracking the reported events in Kenya

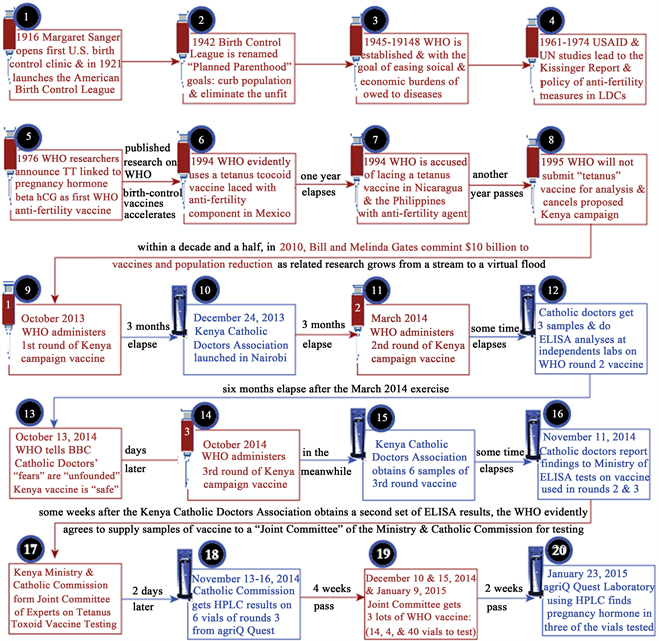

Figure 2 actually begins with milestone events leading up to and through the WHO campaign in Kenya. Event 1 in the top row represents the population reduction efforts of Margaret Sanger beginning in 1916. She described the goal to purify the “gene pool” by “eliminating the unfit”―persons with disabilities [75] . This meant establishing some means of surgical sterilization or otherwise preventing “unfit” persons from reproducing.

Figure 1. A bar graph generated from the Web of Science showing growth through 2015 in the number of citations of the 1994 paper titled “A vaccine that prevents pregnancy in women,” published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and authored by G. P. Talwar and some of the same co-authors on the 1976 paper also in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that debuted the first human testing of a WHO anti-fertility conjugate of the beta chain of human chorionic gonadotropin with tetanus toxoid.

Figure 2. A chronology of milestone events leading up to and including the current research project based on the WHO “tetanus” campaign in Kenya 2013-2015.

By 1942, the American Birth Control League, having been publicly criticized as “anti-family” and “pro-promiscuity”―words used by Mike Wallace while interviewing Sanger on September 21, 1957 [76] ―changed its name to “Planned Parenthood” with Margaret Sanger at the helm from 1952-1959. In the period from 1945 to 1948, after World War II had ended, while the WHO was being conceptualized and becoming the first world-wide subordinate agency under the auspices of the UN, “Planned Parenthood”, headed up by Bill Gates’s father [77] , was promoting the idea that population growth, unless halted or reduced by governmental intervention, would inevitably lead to world-wide famine, disease, the destabilization of governments, and at least one more world war.

In 1961, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) joined with the UN and the WHO in population studies culminating in The Kissinger Report first promulgated as an official classified document to government officials in 1974. In the meantime, moving to the second row in Figure 2, WHO researchers led by Talwar were linking TT to βhCG and testing the first WHO contraceptive vaccine on humans [10] . Then, the years 1993, 1994, and 1995, were marked by news reports of WHO anti-fertility vaccination campaigns in LDCs-specifically, Mexico, Nicaragua and the Philippines [42] [43] [78] [79] [80] , along with a forestalled campaign in Kenya in 1995 [3] ?all of which were represented to the public in those countries, and to the vaccinated females of child-bearing age, as part of the WHO campaign to “eliminate maternal and neonatal tetanus” [56] [57] [58] [59] [60] .

As seen in Figure 2, between events 8 and 9, the $10 billion from the Gates Foundation committed in 2010 was associated by Bill Gates himself with the world-wide population control objective of the WHO to be achieved in part, according to his own words, as noted earlier, with “new vaccines” [71] . Although there is no reason to suppose that other fund-raisers, besides Gates, intended to promote the WHO population control agenda, the targeted regions for the MNT campaigns were effectively the same as the “LDCs” identified earlier in The Kissinger Report. For example, a 2015 news release by Associated Press, announced “immunization campaigns to take place in Chad, Kenya and South Sudan by the end of 2015 and contribute toward eliminating MNT in Pakistan and Sudan in 2016, saving the lives of countless mothers and their newborn babies” [81] .

From event 9 forward, news reports suggested that the WHO had represented an anti-fertility vaccine as a tetanus prophylactic [3] [31] [45] [82] . Throughout the entire chronology of events 9 – 20, the Kenya Ministry of Health and the officials speaking on behalf of the WHO, maintained that the campaign was only to “eliminate maternal and neonatal tetanus” [44] . For example, in his official statement on behalf of the Kenya government, Health Minister James Macharia told the BBC that the WHO Kenya campaign vaccine is “safe” and “certified” and he said “I would recommend my own daughter and wife to take it” [44] .

With the foregoing in mind, in Part 4, we compare the schedules for administering tetanus vaccine as contrasted with those for TT/βhCG conjugate (birth- control) vaccine, and, then, in Part 5 we present and discuss the laboratory findings analyzing samples of the vaccines from the 2013-2015 Kenya campaign as summarized in events 12 – 20 of Figure 2.

4) Comparing vaccination schedules for tetanus and anti-fertility

Table 1 shows the officially recommended intervals for TT shots, including those combined with other antigens such as diphtheria and pertussis [78] . Those intervals differ very little for adults and neonates. The most important difference is that in the case of an unvaccinated woman who is already pregnant, a stepped up schedule for TT is recommended with “the first dose as early as possible

| Optimum dosing interval | Minimum acceptable dosing interval | Estimated duration of protection | |

| Dose un | Au premier contact avec l’agent de santé ou le plus tôt possible pendant la grossesse | Au premier contact avec l’agent de santé ou le plus tôt possible pendant la grossesse | Aucun |

| Dose deux | 6 à 8 semaines après la première dose* | Au moins 4 semaines après la première dose | 1 – 3 ans |

| Dose trois | 6 à 12 mois après la deuxième dose* | Au moins 6 mois après la deuxième dose ou pendant la grossesse subséquente | Au moins 5 ans |

| Dose quatre | 5 ans après la dose trois* | Au moins un an après trois ou pendant la grossesse ultérieure | Au moins 10 ans |

| Dose cinq | 10 ans après la dose quatre* | Au moins un an après quatre ou pendant la grossesse ultérieure | Toutes les années d’âge de procréation; peut-être plus longtemps |

Tableau 1. « Calendrier de vaccination contre l’anonexique du tétanos pour les femmes enceintes et les femmes en âge de procréer qui n’ont pas reçu de vaccination antérieure contre le tétanos », comme rapporté dans Martha H. Roper, J. H. Vandelaer et F. L. Gasse dans The Lancet 2007, 370: 1947-1959.

*Doit être administré plusieurs semaines avant la date d’accouchement s’il est administré pendant la grossesse.

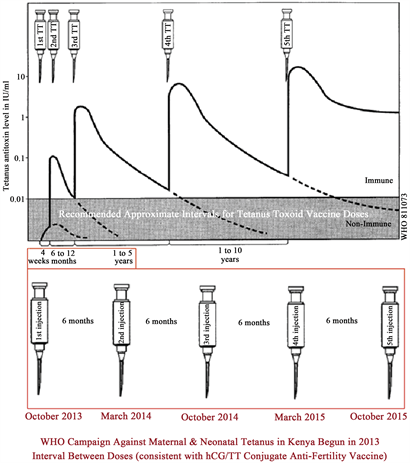

pendant la grossesse et la deuxième dose au moins 4 semaines plus tard » ( [37] , p. 200). Mais contrairement à toutes les recherches publiées sur les inoculations de TT, la campagne de l’OMS au Kenya a espacé de 5 doses de vaccin « TT » à des intervalles de 6 mois, ce qui contrevient, comme l’illustre la figure 3,le calendrier de TT publié à plusieurs reprises. Cependant, le calendrier du Kenya était identique à celui publié pour le conjugué contraceptif de TT de l’OMS lié au βhCG [6] [10] [26] [50] [83] . Le calendrier officiel des doses de TT et les intervalles entre eux dans le tableau 1 ont été publiés dans The Lancet en 2007 pour les filles et les femmes en âge de procréer et pour les nouveau-nés ( [35] , p. 1951) et était inchangé par rapport au calendrier de l’OMS publié en 1993 dans le document intitulé The Immunological Basis for Immunization Series, Module 3: Tétanos, et tel que copié dans la moitié supérieure de la figure 3 [84] .

Les éléments critiques du TT généralisé administré en tant qu’antigène distinct (comme dans le protocole de campagne « tétanos » de l’OMS au Kenya) sont les suivants :

a) La taille officielle de la dose est d’un demi-millilitre du vaccin TT (0,5 ml).

b) Le nombre de doses recommandées pour établir environ 5 ans d’immunité nécessite au moins 3 doses.

c) Et, les intervalles approximatifs entre les 3 premières doses et les doses de « rappel » à suivre (4 injections de plus, ou 7 injections en tout) sont très similaires dans tous les cas à ceux du calendrier pour les nouveau-nés.

Les documents officiels montrent que le calendrier publié par l’OMS pour les doses de TT est conforme à la doctrine « taille unique » du CDC [35] [36] et est essentiellement le même pour tous les receveurs, même si le TT est associé à des antigènes de la coqueluche et de la diphtérie. Le même calendrier publié par l’OMS en 1993 a été copié et réitéré en 2007 [57] [84] et appelle à « trois doses primaires de 0,5 ml »

Graphique 3. Le calendrier recommandé pour l’administration de l’antoxine tétanos d’A.M. Galazka (1993, p. 9, figure 2) [84] en haut contrastait avec le calendrier de l’OMS appliqué dans la campagne du Kenya. Le droit d’auteur sur la figure originale est détenu par l’Organisation mondiale de la santé, mais selon leur avis publié, le document contenant « peut, cependant, être librement révisé, résumé, reproduit et traduit, en partie ou en totalité ».

selon la doctrine standard du CDC qui est contraire à la théorie et à la recherche dose-réponse dans tous les autres domaines de la médecine [85] [86] , et l’une des principales explications de l’omniprésence des troubles auto-immuns associés aux vaccins [87] [88] [89] [90] [91] ― dose unique produite par les fabricants pour tous les receveurs à au moins quatre semaines d’intervalle, suivie de doses de rappel à 18 mois, 5 ans, 10 ans et 16 ans, puis tous les 10 ans » [57] par la suite. Le calendrier de TT pour les adolescents et les adultes, et celui pour les nouveau-nés, nécessitent le traitement de base complet de 7 doses de vaccin, comme indiqué dans le tableau 1 [57] et comme indiqué dans la partie supérieure de la figure 3 où les intervalles entre les doses sont indiqués sur la ligne de temps horizontale. Par conséquent, une question se pose: pourquoi la campagne oms de « tétanos » au Kenya nécessiterait-elle un calendrier radicalement différent de 5 doses à des intervalles de 6 mois, comme le montre la moitié inférieure de la figure 3? Il est intéressant de noter que le calendrier posasé pour la campagne « tétanos » au Kenya 2013-2015 était exactement celui établi pour le conjugué contraceptif de l’OMS contenant du TT/βhCG [2] [9] [36] .

La figure 3 montre les intervalles entre les doses recommandées pour la vaccination contre le tétanos chez les personnes qui n’ont pas été vaccinées auparavant avec une série de vaccins contre le tétanos (dans la moitié supérieure de la figure). Notez que les 5 doses de la campagne de l’OMS au Kenya (dans le plus grand rectangle rouge au bas de la figure 3)seraient administrées en 30 mois, contrairement à la même période ne représentant normalement que 3 doses dans le calendrier de TT recommandé (le plus petit rectangle rouge près du centre de la figure 3). Les intervalles entre les doses de la campagne de l’OMS au Kenya à partir d’octobre 2013 (dans la moitié inférieure de la figure 3)sont radicalement différents du protocole généralisé de l’OMS avec un intervalle d’un mois entre les doses 1 et 2, jusqu’à 12 mois entre les doses 2 et 3, jusqu’à cinq ans entre 3 et 4, ou même 10 ans entre les doses 4 et 5 [42] [70] [74] [75] . Le protocole serait différent, bien sûr, si un individu avait déjà été inoculé, par exemple, avec la série DPT (diphtérie, coqueluche, tétanos) ou toute autre série multivalente contenant du TT au cours des 5 années précédentes, auquel cas, la procédure recommandée serait d’administrer une seule dose (un « rappel » du tétanos) à ne pas répéter jusqu’à 10 ans. Cependant, comme le montre à l’intérieur de la bordure rouge dans environ la moitié inférieure de la figure 3,la campagne de l’OMS au Kenya a impliqué 5 doses de vaccin administrées à des intervalles d’environ 6 mois sur une période de moins de 3 ans.

Moreover, the fact that no males, only females of child-bearing age, were vaccinated in the WHO Kenya campaign seems to imply that tetanospasmin produced by Clostridium tetani cannot infect post-birth males of any age, or females outside the targeted range of 12 to 49 years. The defense that the WHO intended only to target “maternal and neonatal tetanus” seems odd in view of the fact that males are about as likely as females to be exposed to the bacterium which is found in the soil everywhere there are animals. The notion that males, and females outside the child-bearing age range, are less susceptible to cuts, scrapes, and other injuries that might introduce a tetanus bacterium is not credible. But that difficulty is not the only unexplained irregularity in the WHO “tetanus” vaccination campaign in Kenya. Until after the KCCB published its suspicions and preliminary laboratory results confirming them in November 2014 [2] about the WHO “tetanus” campaign underway from October 2013, the following unusual facts made it difficult for the KCDA to obtain the needed vaccine samples for laboratory testing:

・ the campaign was initiated not from a hospital or medical center but from the New Stanley Hotel in Nairobi [92] ;

・ vials of vaccine delivered to each vaccination site for this special “campaign” were guarded by police;

・ handling of vials of vaccine by nursing staff at the site administering the shots was strictly controlled so that when a vial was used up it had to be returned to WHO officials under the watchful eyes of the police in order for the nurse to obtain a new one;

・ vials of WHO “campaign” vaccine were never stored in any of the estimated 60 local facilities but were distributed from Nairobi and used vials were returned there at considerable cost under police escort.

The fact that vials of this particular vaccine had to be stored in Nairobi is peculiar for two reasons: for one, according to the KCDA this is not usually required for vaccine distribution, and, for another, the Kenya Catholic Health Commission (as the medical branch of the KCCB) also manages a network of 448 Catholic health units consisting of 54 hospitals, 83 health centers and 311 clinical dispensaries plus more than 46 programs for Community Based Health and Orphaned and Vulnerable Children scattered all over Kenya’s 224,962 square miles [93] ―an area larger than any US state in the lower 48 except for Texas at 268,601 square miles [94] . In addition, the Catholic Health Commission manages mobile clinics for the nomadic peoples who move about Kenya and into the arid regions of bordering countries. Usually, vaccines in Kenya, according to our physician co-authors (Drs. Karanja and Ngare), would be handled by the nearest hospital, health center, or mobile clinic: why did the particular “tetanus” vaccine used in the MNT campaign of 2013-2015 require so much special handling beginning from the New Stanley Hotel in Nairobi?

In our final part, we present and discuss some of the details of the analyses of 7 vials of vaccine obtained by the KCDA directly from vials being injected in March and October of 2014 during the WHO Kenya 2013-2015vaccination campaign as well as the 52 vials eventually handed over by the WHO to the “Joint Committee of Experts” from vaccines stored in Nairobi.

5) Laboratory Analyses of the WHO vaccines

The original laboratory results of several different enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) previously referred to in various news reports (already cited) along with results from subsequent analyses using anionic exchange high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) are tabled below in this section.

Samples of the WHO “tetanus” vaccine used at the March 2014 administration (event 11 in Figure 2) were disguised as blood serum and were subjected to the standard ELISA pregnancy testing for the presence of βhCG at three different laboratories in Nairobi (event 12 in Figure 2). Results of those analyses are presented in Table 2. Although none of the samples contained enough βhCG to surpass the threshold for a positive judgment of “pregnancy” in a blood sample, all of them tested positive for βhCG above the threshold of zero βhCG expected for a TT vaccine.

At the October 2014 round of WHO vaccinations (dose 3 for participating women shown as event 15 in Figure 2), the KCDA obtained six additional vials of the WHO “tetanus” vaccine and apportioned carefully drawn samples (aliquots) for distribution to 5 different laboratories for ELISA testing with results as shown in Table 3. All but one of the tests showed the presence of βhCG in 3 the 6 samples tested (KA, KB, and KC). Even the PathCare Laboratory, which used less sensitive ELISA kits, ones capable only of measuring international units per liter, IU/L, rather than the more sensitive ELISA kits measuring thousandths of an international unit per milliliter, mIU/ml, found quantities of βhCG in two of the samples (KB and KC) that were well above the expected zero.

| Laboratory Conducting the Analysis | Amount βhCG Detected* | Date Reported |

| Mediplan Dialysis Centers1 | 1.12 mIU/mL | June 30, 2014 |

| Pathologists Lancet Kenya2 | 1.2 mIU/mL | July 6, 2014 |

| University of Nairobi3 | 0.3 mIU/mL | October 22, 2014 |

Table 2. ELISA results for a sample of WHO “tetanus” vaccine obtained by the Kenya Catholic Doctors Association from the March 2014 administration.

*There is a long-standing consensus [95] [96] reflected in available ELISA kits [97] [98] that any amount < 5 mIU/mL is in the normal range for a non-pregnant woman. In the WHO vaccine samples the level of βhCG should be zero. For the sensitivity of ELISA tests to βhCG, see [97] – [102] . 1PO Box 20707, Nairobi, ph. 0726445570, Lab@mediplan.co.ke; 28th Floor-5th Avenue Building, Ngong Road, Nairobi, ph. 0703 061 000 www.lancet.co.ke; 3College of Health Sciences, School of Medicine, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health.

| Independent Laboratories Performing the Tests for βhCG | |||||

| Sample Tested | Mediplan Dialysis Centers | PathCare1* | PathologistsLancet Kenya | Nairobi Hospital2 | Mater Hospital3 |

| KA | 0.80 mIU/mL | 0 IU/L | 0.76 mIU/mL | <1.2 mIU/mL† | <1.2 mIU/mL† |

| KB | 1.16 mIU/mL | 130 IU/L | 0.79mIU/mL | <1.2 mIU/mL† | <1.2 mIU/mL† |

| KC | 1.25 mIU/mL | 30 IU/L | 0.75 mIU/mL | <1.2 mIU/mL† | <1.2 mIU/mL† |

| KD | 0.26 mIU/mL | 0 IU/L | <5 mIU/mL † | 0.305 mIU/mL† | †† |

| KE | 0.09 mIU/mL | 0 IU/L | <5 mIU/mL † | †† | †† |

| KF | 0.14 mIU/mL | 0 IU/L | <5 mIU/mL † | †† | †† |

Table 3. ELISA results for six samples of WHO “tetanus” vaccine obtained by the Kenya Catholic Doctors Association from the October 2014 administration (blank cells mean only that no report was returned to the KCDA).

*The Pathcare cut-off for a positive judgment for pregnancy was >4 IU/L (as also used by the Exeter Clinical Laboratory in England [100] ), which is the same as a negative judgment for <5 mIU/mL as used by the other laboratories with ELISA kits calibrated for mIU/mL with the normal range for a non-pregnant person set at <5 mIU/mL which is the equivalent standard value for the majority of ELISA kits for measuring βhCG, for a few examples see [97] – [102] . †Either the measured βhCG fell below the minimum for a positive pregnancy judgment or the laboratory reported no result implying levels of βhCG in the normal range. ††In these cells, no sample could be delivered to the laboratory because not enough fluid remained in vials KD, KE, and KF. 1Regal Plaza, Limuru, Road, PO Box 1256-00606 Nairobi, enquiries@pathcare.com; 2POBox 30026, G.P.O 00100, Nairobi, Tel: +254(020) 2845000, +254(020) 2846000, hosp@nbihosp.org; 3PO Box 30325, Nairobi, Tel: 531199 3118, no email listed on report.

With the results of Table 2 and Table 3 in hand, on November 11, 2014, the Catholic doctors took their findings to the Kenya Ministry of Health (as WHO surrogates) at an official meeting of Kenya’s “parliamentary health committee” [3] (event 16 in Figure 2). At that meeting, the Cabinet Secretary, James Macharia, rejected the ELISA test findings and expressed “trust” in the WHO and UNICEF [3] . However, the Ministry proposed a follow up by a “Joint Committee of Experts on Tetanus Toxoid Vaccine Testing” to include representatives of WHO on the one hand and the KCDA on the other (event 17 in Figure 2). The Ministry also decided to order high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) retesting the vaccines already in possession of the KCDA having been obtained during the ongoing October 2014 vaccine administration and of which samples had already been tested by ELISA (as shown in Table 3). It was agreed also that additional vials of the Kenya vaccine would be supplied by the WHO for HPLC analysis. The samples already being held by the KCDA and ones to be supplied from the government (WHO) stores were to be delivered to AgriQ Quest Laboratory in Nairobi as verified in the presence of representatives of the “Joint Committee” (including both WHO surrogates and doctors representing the KCCB). AgriQ Quest Laboratory was instructed to determine “if βhCG was present in the submitted vials” (see slide 5 in the official PowerPoint Presentation [62] ), to be reported back to the “Joint Committee” at a date to be announced later by the Ministry.

In fact, two separate sets of HPLC tests would be run by the AgriQ Quest Laboratory. The first set of results, as shown in Table 4, were reported within five days to the KCCB on November 16, 2014 in a document of public record titled Laboratory Analysis Report for the Health Commission, Kenya Conference of Catholic Bishops, Nairobi [63] (event 18 in the chronology of Figure 2). Nine weeks later, after a lapse of 58 calendar days from the time of the setting up of the “Joint Committee”, the WHO surrogates in the Kenya Ministry of Health by-passed the “Joint Committee” contravening their prior commitment and delivered an additional 40 vials of WHO vaccine directly to AgriQ Quest on January 9, 2015. Of the 52 aditional vials allegedly coming from Nairobi supplies to be subjected to HPLC analysis (event 19 in the chronology, Figure 2), the set delivered on January 9, 2015 directly to AgriQ Quest, consisted of 40 vials with the exact same Batch Numbers as the 3 vials that had formerly tested positive for βhCG. We will revisit this fact in the Discussion section below.

Table 5 summarizes results reported by AgriQ Quest to the “Joint Committee” in a document of public record titled Laboratory Analysis Report for the Joint Committee of Experts on Tetanus Toxoid Vaccine Testing [64] and in an oral presentation assisted by a PowerPoint document also of public record on

| Sample tested | AgriQ Quest, Nairobi | |

| Peak retention time for βhCG | βhCG as % of area at peak retention | |

| KA | 36.283 | 37.593 |

| KB | 35.825 | 26.512 |

| KC | 38.042 | 23.939 |

| KD | 36.692 | 0.480 |

| KE | 38.842 | 0.830 |

| KF | 36.425 | 3.334 |

Table 4. Summary of Anionic Exchange High Pressure Liquid Chromatography testing for presence of βhCG in the six samples of WHO “tetanus” vaccine from the October 2014 administration using Detector A (220 nm).

*For all analyses, 100% of each sample was processed in 40 minutes.

| Lot number and source | Batch Number | Expiration Date | Open or closed (number of vials)? | Date samples delivered to AgriQ Quest | Date analysis run at AgriQ Quest |

| Lot 1: from the Kenya WHO Expanded Immunization Program (EPI) Stores, in Nairobi | 019B4002D | January 2017 | Closed (1) | December 10, 2014 | January 5, 2015 |

| 019B4003A | January 2017 | Closed (1) | |||

| 019B4003B | January 2017 | Closed (1) | |||

| 019B4002C | January 2017 | Closed (1) | |||

| 11077A13* | August 2016 | Closed (1) | |||

| 019B4002C | January 2017 | Closed (1) | |||

| 019B4002D | January 2017 | Closed (1) | |||

| 019B4003B | January 2017 | Closed (1) | |||

| 019B4003A | January 2017 | Closed (1) | |||

| 019L3001B† | February 2016 | Open (1)** | |||

| 019L3001C† | February 2016 | Open (1)** | |||

| 019L3001B† | February 2016 | Open (1)** | |||

| 019B4002D | January 2017 | Open (1) | |||

| 019B4003A | January 2017 | Closed (1) | |||

| Lot 2: from Upper Hill Medical Center, in Nairobi | 019B4003A | January 2017 | Open (1) | December 17, 2014 | January 5, 2015 |

| 019B4002D | January 2017 | Open (1) | |||

| 019B4002D | January 2017 | Open (1) | |||

| 019B4002D | January 2017 | Open (1) | |||

| Lot 3: Matching Samples from WHO | 019L3001B† | January 2017 | Closed (10 vials for Pokot tribe) | January 9, 2014 | January 9, 2015 |

| 019L3001C† | January 2017 | Closed (20 vials for Turkana tribe) | |||

| 019L3001B† | January 2017 | Closed (10 vials for Turkana tribe ) |

Table 5. Lots delivered by the Joint Committee to AgriQ Quest for analysis with the nine digit batch number for each vial, its expiration date, whether it was closed or opened when received for analysis, and whether it contained βhCG according to the results obtained.

*This particular vial was the only one from Biological E, Ltd. All other vials were manufactured by the Serum Institute in India. **Judged by analysis to contain βhCG. †Note that the batch numbers on the vials containing βhCG are identical to “matching” vials supplied by the WHO that were tested and did not contain βhCG.

January 23, 2015 [62] 4. Altogether, 58 vials of WHO vaccine were tested. They consisted of the 6 vials previously tested by ELISA and also by HPLC at the request of the Catholic Health Commission (Table 3 and Table 4, respectively). Additionally, there were 52 new samples provided by the WHO as presented in Table 5. Table 4 shows that the first HPLC analyses, conducted at the request of the Health Commission of the KCCB, using the same 6 samples of WHO “tetanus” vaccine from the October 2014 (round 3 administration by the WHO) confirmed the ELISA findings as reported earlier in Table 3. Samples KA, KB, and KC contained βhCG.

The analyses summed up in Table 5, from the second series of HPLC tests, called for by the “Joint Committee”, was run a few weeks after those reported in Table 4. Reading left to right across the rows in Table 5, the sample vials of vaccine are listed by Batch Number, Expiration Date, whether the vial was found to have been Open or Closed upon delivery to AgriQ Quest, the date delivered to AgriQ Quest, and, finally, the date when the analysis was run. Proceeding directly to the question of interest, the 3 vials of the 6 obtained by the Catholic doctors from the WHO vaccine actually used in the October round of injections, the same vials of which samples previously tested positive for βhCG by multiple ELISA analyses and by the HPLC analyses summed up in Table 4, were again found to contain βhCG. They are marked with a double asterisk (**) in the fourth column from the left in Table 5.

By contrast, all 52 additional vials of vaccine delivered to AgriQ Quest by the WHO tested negative for βhCG. More importantly, as noted above, of the 40 samples provided directly to AgriQ Quest by the WHO surrogates on January 9, 2015, the only ones that had the same identifying Batch Numbers as ones containing βhCG from the October 2014 administration, also tested negative for βhCG The reports to the “Joint Committee” on January 23, 2015 [62] [64] by AgriQ Quest (event 20, Figure 2) concluded that only 3 of the 6 vials obtained directly by the Catholic doctors at the round 3 administration in October 2014 contained βhCG (namely those numbered 019L3001B or 019L3001C).

Given the foregoing results, the following facts are known and require explanation:

・ The WHO has been seeking to engineer antifertility vaccines since the early 1970s [5] .

・ Reducing global population growth, especially in LDCs, through antifertility measures has long been declared a central goal of USAID/UN/WHO “family planning” [66] – [77] .

・ Spokespersons associated with the Catholic Church and pro-life groups have published suspicions at least since the early 1990s that the WHO was misrepresenting clinical trials of one or more antifertility campaigns as part of the world-wide WHO project to “eliminate maternal and neonatal tetanus” [3] [41] [42] [43] [45] [92] [103] [104] [105] [106] .

・ Comparison of the published schedules for TT versus TT/hCG conjugate found the WHO dosage plan in the Kenya 2013-2015 campaign to be incongruent with any of those for TT but congruent with published schedules used in TT/hCG research [this paper].

・ Multiple analyses of samples of WHO “tetanus” vaccines, alleged by one or more Catholic spokespersons to have been obtained from vials actually being administered by WHO officials as “tetanus” prophylactics, were found to contain hCG [1] [2] [43] [45] [103] [104] [105] [106] .

・ As recounted in this paper, documents in the public record show that half the vials taken from actual administrations of WHO vaccine during the Kenya campaign in 2014, ones supposedly aimed to prevent MNT, tested positive for βhCG [2] [63] [64] .

An important component of the present investigative research is the discovery of βhCG in some of the vaccine vials used in the WHO campaign in Kenya supposedly aiming to prevent MNT. Possible explanations for the finding of βhCG in those vials include contamination by one or more accidents that might include: 1) a manufacturer’s error in production or labelling; 2) unreliable analysis by the Nairobi laboratories (owing to unclean wells, tubes, gloves, pipette tips, expired or damaged ELISA kits, or poorly calibrated HPLC equipment, inadequately trained laboratory personnel, faulty handling of samples received, mixing of samples, and so on); 3) careless or otherwise inaccurate reporting, or the contaminating βhCG might have been deliberately added by the KCDA seeking to sabotage the WHO anti-fertility efforts by making up false stories about the ongoing “eliminate MNT” project.

Noting immediately that we are relying on reasonable inference to reach the conclusion that we offer at the end of this paper as our opinion, we believe that some of the competing alternatives can be ruled out to narrow the field of possibilities. To begin with, a manufacturing error accidentally getting βhCG in just 3 vials but missing 40 vials from the very same “batch” as judged by the Batch Number is unlikely. Similarly, labeling errors marking just 3 vials containing βhCG with the same label associated with 40 vials not containing βhCG is equally unlikely for the same reason. Batch Numbers are used to track whole lots of vaccines produced on a given run from the same vat of materials in a liquid mixture. Coordinated manufacturing and labeling errors repeated 43 times, 21 times for label 019L3001C and 22 times for 019L3001B, could not be expected to occur by chance but only by intentional design.

Next, there is the possibility of unreliability of handling by laboratory personnel, faulty kits or equipment, and the like. But any explanation attributable to somewhat randomized (unintentional) errors can only account for stochastic variability, e.g., differences across samples of the same vials of vaccine as tested at different laboratories (Table 2 and Table 3) or at different times in the same laboratory (Table 4 and Table 5). However, the myriad sources of unreliability can all be definitively ruled out when the same results for the 6 vials tested repeatedly and independently on different occasions and by different laboratories with more than one procedure give the same pattern of outcomes. In the latter instance, the one at hand, in this paper, we have what measurement specialists call successful triangulation where multiple independent observations by multiple independent observers using multiple procedures of observation concur on a single outcome. In such an instance, all the possible sources of unreliability can be dismissed and we are left only with some non-chance alternatives.

Among the non-chance alternatives we come to the possibility that the KCDA salted the samples of vaccine that tested positive for βhCG. Logically that possibility is inconsistent with the fact that the KCDA had the opportunity to salt the vials and samples for all the ELISA tests and for all 6 of the vials they handed over twice for testing to AgriQ Quest (Table 4 and Table 5). Also, even if the KCDA had access to βhCG so as to add it to just the vials that would test positive for it, such a deliberate mixture before handing samples over to the laboratories for testing would not produce the chemical conjugate found according to AgriQ Quest in the samples that tested positive by HPLC. In their oral report to the “Joint Committee” they described the βhCG they found in those 3 vials as “chemically linked” (on slide 11 of [62] . Such linking is consistent with the patented process for TT/hCG conjugation as described by Talwar [5] [84] , but could not be achieved by simply mixing βhCG into a vial of TT vaccine.

Published works by the WHO and its collaborators continue to encourage and/or sponsor research to generate antibodies to βhCG through “a recombinant vaccine, which would: 1) ensure that the “carrier” is linked to the hormonal subunit at a defined position and 2) be amenable to industrial production” [23] . Such a conjugate has already been achieved with a bacterial toxin (from E. Coli) and can be mass produced with the assistance of a yeast (Pischia pastoris). Also, a DNA version of the new conjugate has already been approved for human use by the United States Food and Drug Administration and has already been used with human volunteers [9] [12] [13] [14] [18] [21] [22] [27] [28] , and WHO’s lead researcher has already claimed success in producing a vaccine against βhCG enhanced with recombinant DNA [17] [21] [22] [23] [24] [107] .

Finally, there is one other reported experimental study that merits mention. One of our anonymous reviewers for a draft version of this paper suggested a host of follow up studies that might be done with the help of recipients of 1 – 5 doses of the Kenya vaccine. One was to measure βhCG antibodies in the blood serum of vaccine recipients downstream from the exposure. If a significant proportion of Kenyan women who received one or more of the WHO “tetanus” injections tested positive for βhCG antibodies, such a result would show that they received βhCG “chemically linked” to some “carrier” pathogen such as TT [108] . This follows because TT by itself would not engender production of βhCG antibodies. Perhaps such a study may be underway in Kenya, or will be done in the future, but the present team of authors lacks the resources to do it. However, such a study from women participants in the WHO “tetanus” vaccination campaign in the Philippines 1993 was already done. J. R. Miller reported that pro-life groups in the Philippines tested the blood sera of 30 of the estimated 3.4 million women vaccinated by WHO in that “tetanus” campaign and 26 of them tested positive for “hCG antibodies” [106] [109] .

Laboratory testing of the TT vaccine used in the WHO Kenya campaign 2013- 2015 showed that some of the vials contained a TT/βhCG conjugate consistent with the WHO’s goal to develop one or more anti-fertility vaccines to reduce the rate of population growth, especially in targeted LDCs such as Kenya. While it is impossible to be certain how the βhCG got into the Kenya vaccine vials testing positive for it, the WHO’s deep history of research on antifertility vaccines conjugating βhCG with TT (and other pathogens), in our opinion, makes the WHO itself the most plausible source of the βhCG conjugate found in samples of “tetanus” vaccine being used in Kenya in 2014. Moreover, given that all vaccine manufacturers and vaccine testing laboratories must be WHO certified, their responsibility for whatever has happened in the Kenyan immunization program can hardly be overemphasized.

Co-authors Felicia M. Clement, Jaimie Ryan Pillette received funding as Ronald E. McNair Research Scholars at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette under US Office of Education Public Grant Award, and Professor John W. Oller, Jr. received a stipend from the same source for serving as their mentor during the semester of their grant (spring 2015) and was partly supported in this work by his endowed position as the Doris B. Hawthorne/LEQSF Professor III at the University of Louisiana.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

The conceptualization of this paper began in January 2015 by the first author in collaboration with Felicia M. Clement and Jaimie Ryan Pillette who jointly presented a preliminary summary of some of the ideas that have been further developed in multiple versions up to the present paper. Drs. Shaw and Tomljenovic agreed to join in the work in May, 2015, writing and rewriting and helping to develop a comprehensive reference list early in the project. In November 2015 we invited the Kenyan medical doctors, Dr. Ngare and Dr. Karanja, to join us and share data they had collected during the World Health Organization 2013- 2015 campaign in Kenya. The bulk of the writing has been done by Oller with edits ranging throughout the development of the manuscript and reported findings by Shaw and Tomljenovic. Drs. Ngare and Karanja contributed data seen in the tables plus detailed explanations about how the data were collected, why certain procedures were followed, and so forth. They also brought a wealth of experience as principals in the Kenya Catholic Doctors Association. As practicing physicians they have been engaged as “boots on the ground” in many parts of the still unfolding narrative reported in this paper. Ms. Clement and Ms. Pillette were involved in the construction of the first draft of the paper and have been included in all of the editorial work through multiple drafts shared between all of the contributors. They are responsible for some of the background information on the programs of the World Health Organization. They were interested in part by the discovery that the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiment that took place in the US from 1932 until 1972 ended in the very year that research on the WHO antifertility vaccines for “family planning” in LDCs was initiated. All authors have accepted responsibility for the content of this manuscript. Any errors remaining are ours alone.

Author affiliations are mentioned on the title page of the paper.

The data referred to in tables in this paper, and the technical reports from which those data are extracted (specifically including those provided to the “Joint Committee of Experts on Tetanus Toxoid Vaccine Testing” referred to in the text) are available upon request from the first author at joller@louisiana.edu.

Abbreviations in Alphabetical Order

BBC = British Broadcasting Corporation;

CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;

DNA = Deoxyribonucleic Acid;

ELISA = Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays;

hCG = Human Chorionic Gonadotropin;

HPLC = High Performance (or High Pressure) Liquid Chromatography;

IU/L = International Units per Liter;

KA, KB, ∙∙∙ KF = Kenya Vials A through F of WHO Vaccine from the October 2014 Administration;

KCCB = Kenya Conference of Catholic Bishops;

KCDA = Kenya Catholic Doctors Association;

LDC = Less Developed Countries (also Used to Refer to “Less Developed Regions” of the World);

mIU/mL = Thousands of International Units per Milliliter;

MNT = Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus;

PubMed = Search Engine of the United States National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health;

TED = Technology, Entertainment, Design (a Media Organization);

TT = Tetanus Toxoid;

TT/βhCG = Tetanus Toxoid Conjugated with Beta Human Chorionic Gonadotropin;

UN = United Nations;

UNICEF = United Nations International Children Education Fund;

US = United States;

USAID = United States Agency for International Development;

WHO = World Health Organization;

αhCG = Alpha Human Chorionic Gonadotropin;

βhCG = gonadotrophine chorionique humaine bêta

1Initialement, plusieurs d’entre nous (Oller, Shaw, Tomljenovic, Clement et Pillette) étudiaient conjointement les porteurs viraux et bactériologiques utilisés pour délivrer des toxiques (par exemple, dans la chimiothérapie anticancéreuse) et / ou des produits médicaux génétiquement modifiés aux cellules et aux tissus des patients humains. Au cours de notre travail, après avoir entendu parler des reportages concernant la campagne de vaccination de l’OMS au Kenya, nous avons trouvé un flux de recherche de longue date publié par l’OMS pour développer des vaccins contraceptifs. Plus tard, nous contacterions les principaux médecins de la KCDA, Karanja et Ngare, qui accepteraient de se joindre à nous dans cette revue et cas d’étude de la campagne de vaccination de l’OMS au Kenya.

2Si, comme le soupçonne l’Église catholique [41] [42] [ 43 ] [44] [45] , l’OMS s’est livrée à une tromperie délibérée exhortant des millions de receveurs d’un vaccin contraceptif à s’exposer à des doses multiples ostensiblement pour éviter la menace de la TM, il est néanmoins probable que de nombreux collaborateurs et partisans de l’OMS ne soient toujours pas au courant de la recherche de l’OMS sur les vaccins contraceptifs, ils sont encore moins susceptibles de connaître la tromperie redoutée par l’Église catholique. Les défenseurs de la recherche antifertilité de l’OMS sur la « planification familiale » peuvent également souligner l’affirmation de G. P. Talwar, le premier chercheur antifertilité de l’OMS, selon laquelle apprendre à prévenir la croissance normale d’un bébé humain peut révéler comment prévenir la croissance anormale d’un cancer [23] parce que certaines des mêmes hormones sont impliquées dans la croissance normale et anormale [46] [47] [48] [49] . Cependant, même si un tel résultat heureux était obtenu, cela justifierait-il la tromperie de l’OMS soupçonnée par l’Église catholique ?

3Les Américains et les Canadiens, Oller, Shaw, Tomljenovic, Pillette et Clement.

4Les trois rapports préparés et présentés par AgriQ Quest au « Joint Committee of Experts on Tetxoid Vaccine Testing », les deux documents écrits et le PowerPoint sont disponibles sur demande auprès de joller@louisiana.edu.

Conflits d’intérêts

Les auteurs ne déclarent aucun conflit d’intérêts.

| [1] | Commission catholique de la santé du Kenya (2017). http://www.kccb.or.ke/home/commission/12-catholic-health- commission-du-kenya/ |

| [2] | (2014) Conférence des évêques catholiques du Kenya. Communiqué de presse de la Conférence des évêques catholiques du Kenya. http://www.kccb.or.ke/home/news-2/press-statement-by-the-kenya-conference-of-catholic-bishops/ |

| [3] | Nzwili, F. (2014) Kenya’s Catholic Bishops: Tet-anus Vaccine Is Birth Control in Disguise. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/religion/kenyas-catholic-bishops-teta-nus-vaccine-is-birth-control-in-disguise/2014/11/11/3ece10ce- 69ce-11e4-bafd-6598192a448d_story.html |

| [4] | Talwar, G.P. (1976) Immunologie dans le domaine de la contraception, y compris l’examen de l’état actuel. Centre régional de documentation sur la reproduction humaine, la planification familiale et la dynamique des populations, Organisation mondiale de la Santé, Bureau régional pour l’Asie du Sud-Est. |

| [5] | Talwar, G.P., Sharma, N.C., Dubey, S.K., Salahuddin, M., Das, C., Ramakrishnan, S., et al. (1976) Isoimmunization against Human Chorionic Gonadotropin with Conjugates of Processed Beta-Subunit of the Hormone and Tetanus Toxoid. Actes de l’Académie nationale des sciences, 73, 218-222. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.73.1.218 |

| [6] | Talwar, G.P. (1979) Progrès récents dans la reproduction et la régulation de la fertilité. Elsevier Science Ltd., New York. |

| [7] | Lall, L., Srinivasan, J., Rao, L.V., Jain, S.K., Talwar, G.P. et Chakrabarti, S. (1988) Recombinant Vaccinia Virus Expresses Immunoreactive Alpha Subunit of Ovine Luteinizing Hormone Which Associates with Beta-hCG to Generate Bioactive Dimer. Indian Journal of Biochemistry & Biophysics, 25, 510-514. |

| [8] | Talwar, G.P. et Raghupathy, R. (1989) Anti-Fertility Vaccines. Vaccin, 7, 97-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/0264-410X(89)90043-1 |

| [9] | Chakrabarti, S., Srinivasan, J., Lall, L., Rao, L.V. and Talwar, G.P. (1989) Expression of Biologically Active Human Chorionic Gonadotropin and Its Subunits by Recombinant Vaccinia Virus. Gène, 77, 87-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1119(89)90362-4 |

| [10] | Talwar, G.P., Singh, O., Pal, R. et Chatterjee, N. (1992) Anti-hCG Vaccines Are in Clinical Trials. Scand J Immunol Suppl, 11, 123-126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3083.1992.tb01634.x |

| [11] | Talwar, G.P., Singh, O., Pal, R., Chatterjee, N., Upadhyay, S., Kaushic, C., et coll. (1993) A Birth-Control Vaccine Is on the Horizon for Family-Planning. Annales de médecine, 25, 207-212. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853899309164169 |

| [12] | Mukhopadhyay, A., Mukhopadhyay, S.N. et Talwar, G.P. (1994) Physiological Factors of Growth and Susceptibility to Virus Regulating Vero Cells for Optimum Yield of Vaccinia and Cloned Gene Product (Beta-hCG). Journal of Biotechnology, 36, 177-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1656(94)90053-1 |

| [13] | Talwar, G.P., Singh, O., Pal, R., Chatterjee, N., Sahai, P., Dhall, K., et al. (1994) A Vaccine That Prevents Pregnancy in Women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 91, 8532-8536. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.91.18.8532 |

| [14] | Giri, D.K. and Talwar, G.P. (1995) Contraceptive Vaccines. Current Science, 68, 423-434. |

| [15] | Mukhopadhyay, A., Mukhopadhyay, S.N. and Talwar, G.P. (1995) Studies on the Synthesis of βhCG Hormone in Vero Cells by Recombinant Vaccinia Virus. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 48, 158-168. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.260480210 |

| [16] | Kaliyaperumal, A., Chauhan, V.S., Talwar, G.P. and Raghupathy, R. (1995) Carrier-Induced Epitope-Specific Regulation and Its Bypass in a Protein-Protein Conjugate. European Journal of Immunology, 25, 3375-3380. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.1830251226 |

| [17] | Srinivasan, J., Singh, O., Chakrabarti, S. and Talwar, G.P. (1995) Targeting Vaccinia Virus-Expressed Secretory Beta Subunit of Human Chorionic Gonadotropin to the Cell Surface Induces Antibodies. Infection and Immunity, 63, 4907-4911. |

| [18] | Mukhopadhyay, A., Talwar, G.P. and Mukhopadhyay, S.N. (1996) Studies on the Synthesis of βhCG Hormone in Vero Cells by Recombinant Vaccinia Virus. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 50, 228. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.260500205 |

| [19] | Talwar, G. (1997) Vaccines for Control of Fertility and Hormone-Dependent Cancers. Immunology and Cell Biology, 75, 184-189. https://doi.org/10.1038/icb.1997.26 |

| [20] | Talwar, G.P. (1997) Fertility Regulating and Immunotherapeutic Vaccines Reaching Human Trials Stage. Human Reproduction Update, 3, 301-310. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/3.4.301 |

| [21] | Purswani, S. and Talwar, G.P. (2011) Development of a Highly Immunogenic Recombinant Candidate Vaccine against Human Chorionic Gonadotro

pin. Vaccine, 29, 2341-2348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.069 |

| [22] | Nand, K.N., Gupta, J.C., Panda, A.K., Jain, S.K. and Talwar, G.P. (2015) Priming with DNA Enhances Considerably the Immunogenicity of hCG β-LTB Vaccine. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 74, 302-308. https://doi.org/10.1111/aji.12388 |

| [23] | Talwar, G.P. (2013) Making of a Vaccine Preventing Pregnancy without Impairment of Ovulation and Derangement of Menstrual Regularity and Bleeding Profiles. Contraception, 87, 280-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2012.08.033 |

| [24] | Talwar, G.P., et al. (2014) Making of a Unique Birth Control Vaccine against hCG with Additional Potential of Therapy of Advanced Stage Cancers and Prevention of Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Journal of Cell Science & Therapy, 5, 159. https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7013.1000159 |

| [25] | Alkema, L., Kantorova, V., Menozzi, C. and Biddlecom, A. (2013) National, Regional, and Global Rates and Trends in Contraceptive Prevalence and Unmet Need for Family Planning between 1990 and 2015: A Systematic and Comprehensive Analysis. The Lancet, 381, 1642-1652. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62204-1 |

| [26] | Talwar, G.P., Gupta, J.C., Rulli, S.B., Sharma, R.S., Nand, K.N., Bandivdekar, A.H., et al. (2015) Advances in Development of a Contraceptive Vaccine against Human Chorionic Gonadotropin. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy, 15, 1183-1190. https://doi.org/10.1517/14712598.2015.1049943 |

| [27] | Gupta, A. (2001) High Expression of Human Chorionic Gonadotrophin Beta-Subunit Using a Synthetic Vaccinia Virus Promoter. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology, 26, 281-287. https://doi.org/10.1677/jme.0.0260281 |

| [28] | Rout, P.K. and Vrati, S. (1997) Oral Immunization with Recombinant Vaccinia Expressing Cell-Surface-Anchored βhCG Induces Anti-hCG Antibodies and T-Cell Proliferative Response in Rats. Vaccine, 15, 1503-1505. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-410X(97)00094-7 |

| [29] | Walther, W. and Stein, U. (2000) Viral Vectors for Gene Transfer: A Review of Their Use in the Treatment of Human Diseases. Drugs, 60, 249-271. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200060020-00002 |

| [30] | Xie, Y.C., Hwang, C., Overwijk, W., Zeng, Z., Eng, M.H., Mule, J.J., et al. (1999) Induction of Tumor Antigen-Specific Immunity in Vivo by a Novel Vaccinia Vector Encoding Safety-Modified Simian Virus 40 T Antigen. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 91, 169-175. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/91.2.169 |

| [31] | Smith, S. (2016) Catholic Doctors Claim UN Aid Groups Sterilized 1 Million Kenyan Women with Anti-Fertility-Laced Tetanus Vaccinations. CP World. http://www.christianpost.com/news/catholic-doctors-claim-un-aid -groups-sterilized-1-million-kenyan-women-with-anti-fertility-laced-tetanus- vaccinations-129819/ |

| [32] | Correa Diaz, A.M. and Valencia Arias, A. (2016) Social Responsibility and Ethics in Medical Health. Ratio Juris, 11, 73-89. |

| [33] | Casey, M.J., O’Brien, R., Rendell, M. and Salzman, T. (2012) Ethical Dilemma of Mandated Contraception in Pharmaceutical Research at Catholic Medical Institutions. The American Journal of Bioethics, 12, 34-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2012.680532 |

| [34] | Bonebrake, R., Casey, M.J., Huerter, C., Ngo, B., O’Brien, R. and Rendell, M. (2008) Ethical Challenges of Pregnancy Prevention Programs. Cutis, 81, 494-500. |

| [35] | Etchells, E., Sharpe, G., Walsh, P., Williams, J.R. and Singer, P.A. (1996) Bioethics for Clinicians: 1. Consent. CMAJ, 155, 177-180. |

| [36] | Newton-Howes, P.A., Bedford, N.D., Dobbs, B.R. and Frizelle, F.A. (1998) Informed Consent: What Do Patients Want to Know? New Zealand Medical Journal, 111, 340-342. |

| [37] | Nisselle, P. (1993) The Right to Know—The Need to Disclose. Australian Family Physician, 22, 374-377. |

| [38] | Miziara, I.D. (2013) ética para clínicos e cirurgioes: Consentimento. Revista da Associacao Médica Brasileira, 59, 312-315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ramb.2013.06.007 |

| [39] | Guseinov, A.A. (2013) The Golden Rule of Morality. Russian Studies in Philosophy, 52, 39-55. https://doi.org/10.2753/RSP1061-1967520303 |

| [40] | Corazzini, K.N., Lekan-Rutledge, D., Utley-Smith, Q., Piven, M.L., Colón-Emeric, C.S., Bailey, D., et al. (2005) The Golden Rule: Only a Starting Point for Quality Care. Director, 14, 255-293. |

| [41] | Ness, G.D. (1994) Worlds Apart 2: Thailand and the Philippines. Heroes and Villains in an Asian Population Drama. People Planet, 3, 24-26. |

| [42] | (1995) Tiff over Anti-Tetanus Vaccine Now Erupted into Battle. International/ Philippines. Vaccine Wkly, 11-13. |

| [43] | (1994) Philippines. Church vs. State: Fidel Ramos and Family Planning Face “Catholic Power.” Asiaweek, 21-22. |

| [44] | Kenya Catholic Church Tetanus Vaccine Fears “Unfounded.” BBC News. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-29594091 |

| [45] | West, T. (2014) Kenyan Doctors Find Anti-Fertility Agent in Tetanus Vaccine? Catholic Church Says Yes. The Inquisitr News. http://www.inquisitr.com/1593224/kenyan-doctors-find-anti- fertility-agent-in-tetanus-vaccine-catholic-church-says-yes/ |

| [46] | Liu, R., Li, X., Xiao, W. and Lam, K.S. (2017) Tumor-Targeting Peptides from Combinatorial Libraries. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 110, 13-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2016.05.009 |

| [47] | Zhang, X. and Xu, C. (2011) Application of Reproductive Hormone Peptides for Tumor Targeting. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, 12, 1144-1152. https://doi.org/10.2174/138920111796117427 |